Article written by Petrus van Niekerk with support from his teacher Chris Ahlfeldt as part of the Environmental Finance Course with the University of Stellenbosch Business School.

Many municipalities in South Africa are cash-strapped with ever-growing populations and increasing urbanisation, causing them to struggle to keep up with service delivery and sustainable development. Their unsustainable municipal business models further show the growing need for financing climate change adaptation programmes. South Africa has seen a major increase in climate-related disasters over the past decade, including major flooding experienced in the Gauteng city-region, severe drought in various locations including Cape Town that nearly led to a dangerous deficit in potable water, and the largest recorded wildfires in South African history in the Garden Route in 2017 and 2018 (WWA, 2018; NMU, 2019; Floodlist, 2020). As with most climate disasters, the poorest communities are hit hardest with long-term damage and extended livelihood recovery periods. The need for innovative climate finance that can be deployed at scale is palpable.

This paper reviews selected literature on green bonds as a climate finance tool and combines a literary review with a closer look at several recent South African examples. The central question I explore is: Do green bonds represent a viable climate finance innovation that can be deployed successfully in the public sector to significantly impact climate change adaptation?

What is a Green Bond?

A green bond is a structured finance tool used by organisations to fund programmes and projects that are perceived to be environmentally responsible. According to the World Bank’s definition, a green bond is “a debt security that is issued to raise capital specifically to support climate-related environmental projects” (World Bank, 2018). The Climate Policy Initiative regards green bonds as a well-established climate finance tool that has made a significant contribution to addressing climate finance constraints since its inception (Buchner et al., 2017). Investment in renewable energy is regarded as a major component of climate change adaptation, and according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), green bonds can assist in opening capital market access and attract greater liquidity and long-term finance for the renewable energy sector (IRENA, 2018).

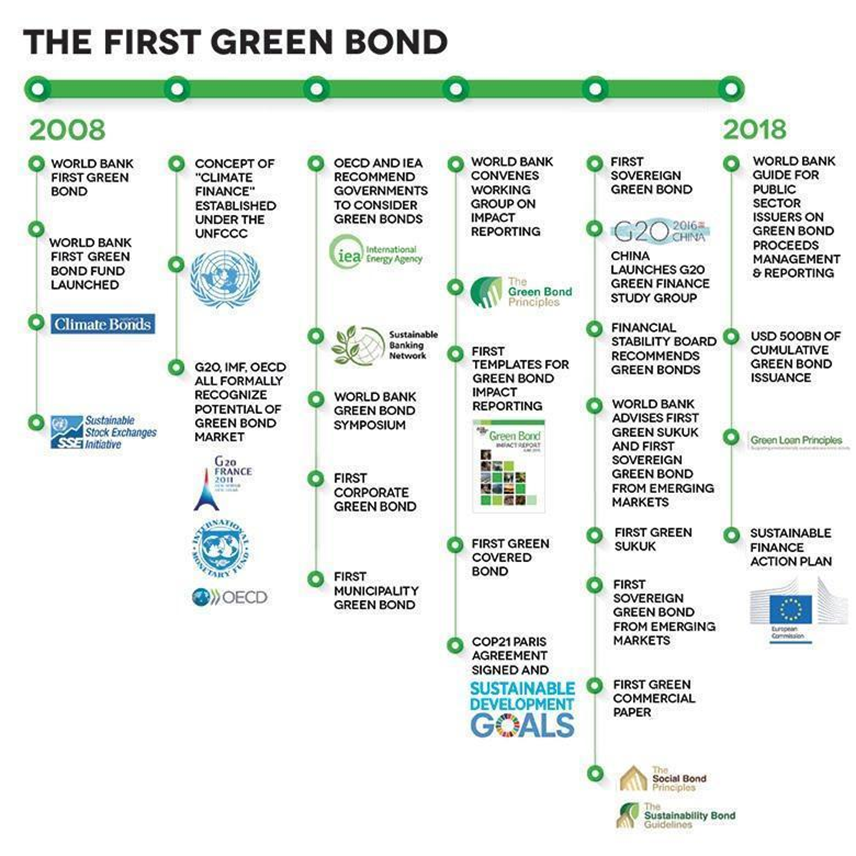

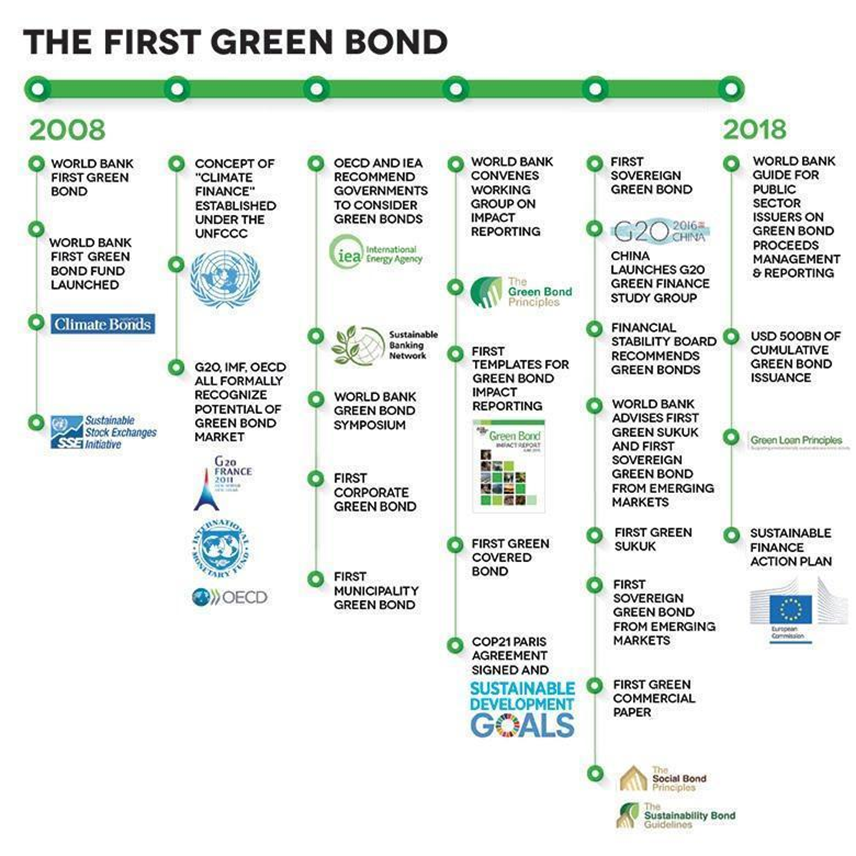

The green bond market was initiated in 2007/2008 with an AAA-rated issuance from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the World Bank (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2021). In 2013 the wider bond market reacted to a large green bond issuance by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the first $1 billion green bond. This was then followed by the issuing of corporate green bonds by large corporations active in sectors ranging from property development, railway infrastructure, technology companies, and more. The infographic below depicts this evolution.

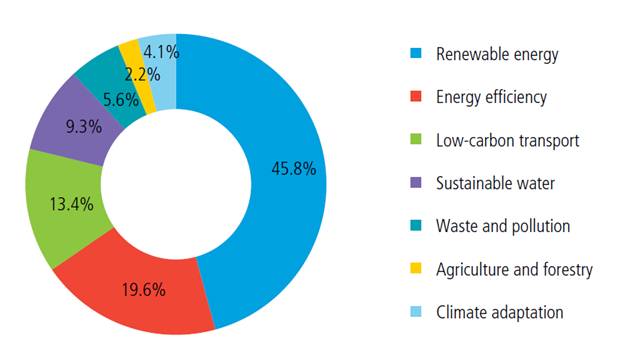

As depicted in the infographic the institutional and governance framework of green bonds has matured considerably since 2008 with guidelines for impact reporting and various action plans that promote green bond issuing and provide technical advisory support for their implementation. Looking at the public sector, or more specifically municipal green bonds, the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) deserves a mention. The CBI is an important non-governmental organisation that assists governments and investors in issuing green bonds and assists in certifying eligible green projects for the bonds. The CBI has a particular taxonomy of green bond project certification which includes a broad range, including renewable energy, green properties, low-emissions transport infrastructure, water efficiency projects, and more.

Which projects are financed with green bonds?

Can Green Bonds help address local governments’ climate change adaptation programmes?

According to the Finance for City Leaders Handbook issued by the United Nations, “as with any other bond, the bond issuer raises a fixed amount of capital from investors over an established period, repays the capital when the bond matures and pays an agreed-upon amount of interest during that time.”Green bonds therefore provide an opportunity for municipalities to raise large amounts of capital to finance their climate change policies outside of their normal revenue streams, and thankfully, an adequate market appetite exists for these bonds.

The City of Johannesburg leads public sector green bond issuance in South Africa

In 2013/2014, the City of Johannesburg (CoJ) became the first South African municipality to list a green bond on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange (JSE). The bond was valued at R1.46 billion and priced 1.85% above the popular South African government savings bond, and its auction was a major success that saw an oversubscription rate of 150%. The CoJ raised the capital to finance initiatives including a biogas to energy plant, a solar water heater programme, and other projects that show quantifiable green-house gas emissions reductions aligned to the City’s climate change mitigation strategy (City of Johannesburg, 2014). Cape Town, another major metropolitan municipality, followed suit not long after.

The City of Cape Town Follows Johannesburg’s Lead

In July 2017, the City of Cape Town’s green bond went on auction. According to the City, “within two hours, 29 investors made offers totaling R4,3 billion in response to the R1 billion that was being sold. The R1 billion cleared at 133 basis points above the R186 government bond.” The City’s green bond was certified by the CBI and Moody’s international rating agency rated it as ‘Excellent’ by assigning a GB1 rating (City of Cape Town, 2017).

The projects earmarked for funding through the green bond included a variety of climate change mitigation and adaptation initiatives that aligned to the City’s Climate Change Strategy. Some of these projects include (City of Cape Town, 2017):

- Procurement of electric buses

- Energy efficiency in buildings

- Water management initiatives (includes water meter installations and replacements, water pressure management, and reservoir upgrades)

- Sewage effluent (sewage discharged into bodies of water) treatment

- Rehabilitation and protection of coastal structures

The City made use of a qualified private-sector intermediary that listed and marketed the bond via the JSE. It also ensured the capital-raising process complied with the South African Municipal Financial Management Act of 2003 and that the related project management protocols were aligned to the Municipal Systems Act of 2000. This is an important point since governmental regulations are often perceived as a stumbling block for unlocking innovative finance.

Expenditure and project performance are tracked through the City’s existing enterprise resource planning (ERP) system that includes detailed breakdowns of project milestones and deliverables linked to expenditure. According to the City’s Green Bond Framework, in order to identify the right programmes/projects that would benefit from green bond capital, the following criteria were examined:

- Identification of significant projects (>ZAR 1,000,000 Capital Expenditure)

- Assessment of current source of finance (budgeted and/or allocated) to determine the ease and consequences of possible re-financing (grant-funded projects will not be considered).

- Alignment of remaining programmes/projects/assets to existing Climate Bond Certification Criteria.

- Alignment with the City’s Environmental Strategy (2016), Implementation Framework (2016), and Draft Climate Change Policy (2016) implementation.

- Ease of access to evidence for assessment of project/asset against Climate Bond Certification Criteria” (Source: City of Cape Town Green Bond Framework, 2017)

Sub-national green bond planning: the Western Cape municipal energy resilience project

The Western Cape Infrastructure Investment Framework (created in 2013) estimates R600 billion will be required for infrastructure investment in the Western Cape between 2018 and 2040. Planning documents from 2018 indicate that the Western Cape government is planning a regional governmental green bond issuance that would finance green infrastructure investment and that local municipalities in the province could be supported to cover the financing gaps that exist to build this infrastructure (Western Cape Government, 2018).

The success of the green bond programmes in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and the Western Cape demonstrates the potential effectiveness of green bonds and suggest growth in popularity as an innovative climate finance tool. But will it last?

Many Shades of Green: Are sustainability (green) bonds sustainable?

Green bonds have shown their efficacy in both public and private sectors around the globe, but some analysts argue that the difference between normal corporate or sovereign bonds and green bonds is minimal (Dontas & Moore, 2020). For one, the financial returns on both bonds are very similar (green bonds would not be used otherwise), and investors in green bonds are often the same as those who would invest in normal bonds. The infographic below shows the similarities and differences between green bonds, social bonds, and sustainability bonds. Collectively these can be described as the growing target market for environmental, social, and corporate/governance (ESG)-linked bond investors.

Since the projects financed through a green bond and its two siblings vary greatly, one could argue that the perception and connotation of being a responsible investor who promotes responsible investments is what has led to the growing popularity of green bonds as a financing instrument. The evolution and development of the ESG-linked bond market is expected to impact the use of these bonds in the future.

Market analysts believe that investment-grade ESG bonds will experience the development of more independent oversight requirements, better impact reporting mechanisms using more real-time tech-enabled performance management platforms, and fine-tuning ESG bond rating details to ensure that organisations making use of this financing mechanism are held accountable and comply with the ‘green’ intentions of the bond programme (Dontas & Moore, 2020).

Governmental organisations in South Africa, in particular local governments, are well-versed in impact reporting as they are held accountable for tax expenditure on public services on a regular basis. As seen in the City of Cape Town case, its existing ERP system provided for transparent and regular impact reporting on green bond-funded projects. This is an area where some local authorities can provide insight for the ESG-linked bond market development in the future.

Conclusion

Green, social, and sustainability bonds are here to stay given their growing popularity among ESG-conscious financiers and the global trend towards more responsible investment practices. Governments, particularly cities, have a mandate to provide basic services and urban development planning and need to follow through by embracing climate change mitigation. Municipalities in South Africa face severe financial constraints to respond to this challenge, but through the recent success of the City of Johannesburg and City of Cape Town’s green bond programmes and planning a provincial green bond programme in the Western Cape, municipalities are sending positive signals to the rest of the sub-national government sector that green bonds can plug the financing gap and enable prudent climate change adaptation action.

References

Buchner, B., Oliver, P., Wang, X., Carswell, C., Meattle, C., & Mazza, F. (2017). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2017. Climate Policy Initiative. CPI Report, October 2017. Retrieved from: https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017-Global-Landscape-of-Climate-Finance.pdf

Business Tech. (2021). These six municipalities are moving off Eskom’s grid and away from load shedding. Retrieved from: https://businesstech.co.za/news/energy/476238/these-six-municipalities-are-moving-off-eskoms-grid-and-away-from-load-shedding/

City of Johannesburg. (2014). Joburg Pioneers Green Bond. Retrieved from: https://www.joburg.org.za/media_/Newsroom/Pages/2014%20Articles/Joburg-pioneers-green-bond.aspx.

City of Cape Town. (2017). City of Cape Town Green Bond Framework. Retrieved from: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/files/Cape%20Town%20Green%20Bond%20Framework.pdf

City of Cape Town. (2017). Green pays: City’s R1 billion bond a resounding success in the market Retrieved from: https://www.capetown.gov.za/media-and-news/Green%20pays%20City

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2021). Explaining Green Bonds. Retrieved from: https://www.climatebonds.net/market/explaining-green-bonds

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2015). Scaling up Green Bond Markets for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/files/GB-Public_Sector_Guide-Final-1A.pdf

Dontas, S., & Moore, L. (2020). How green are green bonds? Retrieved from: https://am.jpmorgan.com/sg/en/asset-management/liq/insights/portfolio-insights/fixed-income/fixed-income-perspectives/how-green-are-green-bonds/

FloodList. (2020). South Africa – Floods Cause Havoc in Johannesburg and Gauteng. Retrieved from: http://floodlist.com/africa/south-africa-floods-johannesburg-gauteng-february-2020

IRENA. (2018). Global Landscape of Renewable Energy Finance, 2018, International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi.

Mining.com. (2020). Green, social and sustainability bonds to reach $400 billion in 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.mining.com/green-social-and-sustainability-bonds-to-reach-400-billion-in-2020/

Nelson Mandela University. (2019). What caused the Knysna wildfires? Retrieved from: https://news.mandela.ac.za/News/What-caused-the-Knysna-wildfires

Ngwenya N, Simatele MD. (2020). The emergence of green bonds as an integral component of climate finance in South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 116(1/2), Article e6522. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2020/6522.

Western Cape Government. (2019). Sub-national green bonds. Innovation finance for sustainability. Retrieved from: https://www.salga.org.za/dev/miif/Presentations/2%20WCG%20GB%20SPV%20SALGA.pdf

World Bank Group. (2018). Strategic use of climate finance to maximise climate action: A guiding framework [webpage on the Internet]. c2018 [cited 2019 May 26]. Retrieved from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30475?locale-attribute=fr

World Bank Group. (2019). 10 Years of Green Bonds: Creating the Blueprint for Sustainability Across Capital Markets. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2019/03/18/10-years-of-green-bonds-creating-the-blueprint-for-sustainability-across-capital-markets. World Weather Attribution. (2018). Likelihood of Cape Town water crisis tripled by climate change. Retrieved from: https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/the-role-of-climate-change-in-the-2015-2017-drought-in-the-western-cape-of-south-africa/